This tale is adapted from the story “Fisherman Plunk and His Wife” by Ivana Brlić-Mažuranić which can be found in Croatian Tales from Long Ago. Ivana Brlić-Mažuranić is considered the Hans Christian Anderson of Croatia and every year her hometown, Ogulin—as haunted a landscape as ever there was one—holds a fairy festival. I hope that my reinterpretation does justice to the original tale.

Amber Joy

Now, you don’t travel for any length of time in the woods without learning a bit about magic, and the fisherman’s wife had spent a fair significant amount of time traveling through and living in the woods and wilds of the mountains with her mother. Them having lost their home—humble though it was—to her father’s debts when he passed from this life to the next. She and her mother lived by wit and will, trading herbs and simples, traveling through and searching for a place they could call home again. And while they were traveling, the fisherman’s wife learned something of the rhythm and flavor of magic. Enough to be able to feel it when it stirred, and she could feel it stirring ever since her husband disappeared for three days and nights. When he ran out of the house before the sun had even cleared the horizon on the day of the New Moon. She knew something seriously magical was going on with her husband.

She prayed, without much hope, that she was wrong.

It wasn’t so much the magic that worried her—though before her time in the woods it would have. It was the creatures of magic—gods, fairies, goblins, and the like—were so unhuman. They were so very different and that difference often made them dangerous. If her husband were trafficking with a creature like that, well, it could explain his completely irrational actions of late. He was a simple fisherman, steady, reliable, sweet, and, yeah, a bit foolish. He could hardly handle dealing with so alien a being. Even the wisest man didn’t come away unscathed from interactions with most spirits. Not unless that spirit allowed them to get away unscathed.

The fisherman’s wife waited three days and nights, hoping that her fears were unfounded and that her husband would come home. When dawn broke at the end of the third night she knew that she had to do something to rescue the fool and she set about to do just that.

There was bit of a problem with her plan, though: being neither a fairy-woman nor a witch the fisherman’s wife had no idea how to go about saving her husband. She had no idea how to even find her husband. She knew neither the first step nor the last. But fishermen aren’t the only ones with spells, any fairytale will tell you that daughters who lost their mothers have their own bit of magic. So when she couldn’t think of anything else, the fisherman’s wife found herself in the mountains, weeping and pouring out her heart’s troubles on her mother’s grave.

As she wept, the fisherman’s wife was approached by a hind that looked at her with the eyes of her mother. It spoke to her silently, in the way animals speak with each other, but also with the voice of her mother.

“Daughter,” it said, “you are right to think your husband is in dire straits, but it is of his own making. Is it worth the danger you’ll put yourself in to save him? It won’t be easy, you know.”

“I know,” the fisherman’s wife answered, “but I like my life with him in it and my son deserves to know his father. I love him, so what else can I do?”

The hind snorted and the woman heard in her head, “Love, hm? Well, I suppose there’s nothing for it. I’ll help you all I can, though I doubt you’ll thank me for it.

“For the next three turns of the moon, go out at dawn to the cliff above your house with the food you’d normally feed your husband and a length of the fine hemp line that he would use in his boat. Sit. Set down the plate and unpick the line. Call to the creatures of earth and sky to come and take what they will. Let them come and do just that. Once they’re gone, if there’s anything left, take it for yourself. It may be of some use.”

The fisherman’s wife did as she was told and at dawn the next day, with her son on her back, she went to the cliff above her house with a plate of food and a length of rope. She sat, set the food on the ground, and began to pick apart the rope. As she did so, she called to the creatures of the earth to take what they would. Soon she was surrounded by snakes: big and small snakes, old and young snakes, garden snakes and vipers. They wriggled and squiggled and slithered and slid around and over her. Up to the plate they went for a bite of food and away again, some even wriggling out of their skin. And when all the snakes had had their fill there was a single bite left, which, remembering her mother’s words, the fisherman’s wife took and ate herself.

By then the rope was untwined and so the fisherman’s wife called to the creatures of the air to come and take what they would. Soon she was surrounded by birds: large birds, small birds, raptor and wrens, humming birds, magpies, ravens and hens. They fluttered and flittered and flew all about picking up bits of hemp to use in their nests. Some leaving a feather or two behind when they left. And when all the birds had come and gone the fisherman’s wife gathered what was left of the hemp, the skins the snakes had shed, and what feathers she found and went about her chores for the day.

That evening, after she set her son to bed, she looked at what she gathered and thought about what to do with it. The hemp she twisted into a length of rope, smaller and thinner than it had been, but perhaps it would be useful still. The skin and feathers she took and began to pattern a cloak out of them.

The next day she did the same and the next after that. And every evening she twisted a little more rope and added a bit more to her cloak. By the end of a week she had seven thin ropes of the same length and the hood and collar of her cloak made. One week turned to two, turned to three, became a month and then another. Thrice the moon waxed and waned, and found the woman once again at the grave of her mother. This time, with cloak of feathers and snakeskin long enough to cover three people and 84 lengths of rope. As her tears fell on her mother’s grave, the fisherman’s wife was once again approached by a hind that looked at her with her mother’s eyes.

“Have I done enough, Mother?” she asked the hind, “Will you tell me how to rescue my husband now?”

“Are you sure you want to go?” the hind answered, “The journey is long and perilous. You may not survive and if you should die your son will too.”

“I will go and I will succeed. What choice do I have of it? I do still love him you know.”

The deer huffed an all to human sigh and said, “As you wish. Your husband is caught under the Unknown Sea, as jester in the Sea King’s palace. The tears he’s shed for want of you and what he had have added to the volume of the sea, increasing the Sea King’s wealth. The King will not let go of him so easily, not when he has value left to add or pleasure left to give. Are you positive you wish to challenge the Sea King by taking his new toy?”

“I must get my husband back.”

“Very well, you must take a boat to the Unknown Sea. To get there without the guidance of a god is very difficult. You must pass through three caverns disguised as terrible stormclouds. These caverns are guarded by three monsters: one who troubles the sea and stirs the waves, one who raises the storm, and a third who flashes and weilds lightning. It is unlikely that you will survive even one of those monsters and once you start there is no turning back.

“If you manage to get past the guardians, you will find yourself in the Unknown Sea. Sail until you can no longer see the storm, then heave to and play the fisherman. Drop a line in the water, your husband’s bone hook at the end of it and wait. What you catch you can keep—if you can hang on to it. I don’t know how to escape the Unknown Sea, you’ll have to figure that out for yourself. No mortal ever managed it, so as much as I wish you luck, Daughter, I mourn your future if you continue on this path. Will you not reconsider?”

“I won’t.”

“You are as foolish as your man.”

“Maybe. What direction should I sail?”

“It doesn’t matter. If you mean to enter the Unknown Sea either you’ll find it or you won’t. Take nothing but what you’ve made these last three months and you’re husbands bone hook and line.”

“Goodbye, Mother.”

“Good luck, Daughter.”

With that the fisherman’s wife left her mother’s mountain grave and the hind behind her and walked back to her little house by the sea. There she gathered her son, her cloak, her rope, and her husband’s bone hook and line and packed everything in the little boat the fisherman made her the first year they were married and set out to find the Unknown Sea. She sailed with the wind when their was wind and drifed with the current when there wasn’t. Day became night became day again and again and again. When the wind blew cold and rains fell she covered herself and her son up with the cloak she made and pushed on. When they were bored or scared she told stories and when her son was asleep, to keep her hands busy and her mind off the danger she’d put them both in, she wove and knotted the 84 lengths of rope together and prayed she haden’t killed them both.

After three days she had no more rope and a wall of black and stormy cloud ahead of her. She aimed her little boat right at the stormcloud, held her breath, and sailed straight in. The cloud parted as if it wasn’t there and the fisherman’s wife found herself before a fierce dark cavern. Inside the cavern was a great, large snake, the Mother of All Snakes—her head blocked the entrance to the cavern and her long, terrible body was coiled up within, her tail lashed the sea, troubling the waters and stirring up the waves.

The fisherman’s wife was afraid but determined.

“Please let me through,” she begged the great snake. “I need to find my husband.”

“No, woman,” said the snake, “turn back and find yourself a different husband. Leave now before I send a wave to capsize your boat.”

“I cannot. I need to find my husband. Let me through. I have spent the last several months feeding your children, surely that counts for something. Please.”

“Ah,” the great snake said, “I see their sheds in your cloak, so I know you speak the truth. Here, take these strings of sapphire and pearls—they regenerate so as soon as you spend one another grows, you will have wealth the rest of your days if you take these as recompense and begone!”

“I do not need pearls and sapphires or even wealth everlasting—though some wealth would be nice. Letting me through will be more than payment enough. I must go to my husband. I love him, you see.”

“I suppose there’s no help for it,” sighed the snake, “I will let you pass this once, but should I see you again I will make such a wave as the world has never seen. Your boat will capsize and sink and you will be food for the Dark Deeps.”

Then the snake slithered away from the entrance and allowed the fisherman’s wife to pass. She followed the cavern back, back, back and through an opening just big enough to allow her boat to pass. Then she sailed on.

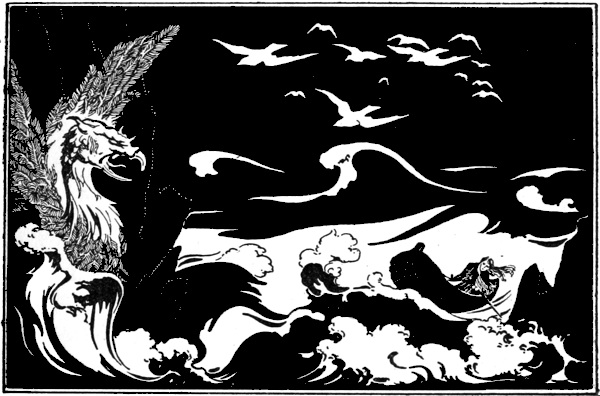

And lo! After three days the fisherman’s wife found herself before another wall of cloud. In she sailed and the cloud parted as if it were never there and the fisherman’s wife found herself in front of a fierce, dark cavern. In the second cavern there was a monstrous Bird, the Mother of All Birds. She craned her frightful head through the opening, her iron beak gaped wide; she spread her vast wings in the cavern and flapped them, and whenever she flapped her wings she raised a storm.

The fisherman’s wife steeled herself and asked for entrance into the cavern as she had the snake. As the snake had, the bird denied her.

“Please let me through,” she begged the bird. “I need to find my husband.”

“No, woman,” said the monstrous bird, “turn back and find yourself a different husband. Leave now before I send a storm to destroy your boat.”

“I cannot. I need to find my husband. Let me through. I have spent the last several months helping your children build their nests, surely that counts for something. Please.”

“Ah,” the terrible bird said, “I see their feathers in your cloak, so I know you speak the truth. Here, I will give you and your son a drink from the waters of eternity. You will be granted eternal youth and health for all the days of the world. Take this in recompense and be on your way.”

“I do not need eternal youth and though health is always welcome, letting me through will be more than payment enough. I must go to my husband. I love him, you see.”

“I suppose there’s no help for it,” sighed the bird, “I will let you pass this once, but should I see you again I will stir such a storm as the world has never seen and you will be destroyed.”

With that the bird hopped away from the entrance and allowed the fisherman’s wife to pass. She followed the cavern back, back, back and through an opening just big enough to allow her boat to pass. Then she sailed on.

When again she found herself before a wall of cloud, the fisherman’s wife pushed through. The cloud melted as if it were never there and she found herself in front of the final cavern. Blocking the entrance to the third cavern was a great golden bee. The Golden Bee buzzed in the entrance; she wielded the fiery lightning and the rolling thunder. Sea and cavern resounded; lightning bolts flashed from the bee to the cave to the sky to the sea seemingly at random.

“Please let me through,” she begged the bee. “I need to find my husband.”

“No,” said the bee and lightning struck the water just in front of the bow of the boat.

The fisherman’s wife’s teeth hummed and all her hair stood on end. She was very worried. She hadn’t helped out any bees in the prior months. The bee was not demanding she go back. It just buzzed and zig-zagged and threw lightning willy-nilly. The lightning increased in frequency and though it still seemed to strike at random it was definitely getting closer and closer to the boat. The fisherman’s wife couldn’t go forward and she couldn’t go back. All seemed lost, then she moved her hand and felt the rope she’d been knotting and weaving together throughout her journey. She seized it and cast it over the bee. The lightning stopped and the bee cried out.

“Let me go, woman!” the bee shouted.

“No,” said the fisherman’s wife and she sailed through the cavern. Back, back, back and through a small opening no bigger than her boat. Once through safely she released the bee and retrieved her net thinking such a thing is very useful. Then she sailed on.

She sailed and sailed until she could no longer see the stormcloud caverns and there she hove-to, set her hook to a line and the line in the water, and waited to see what she caught.

While his wife journeyed to rescue him, the fisherman, sick and tired and very, very frightened, plotted his escape. It was obvious to him that the Sea King was beginning to tire of his antics and he began to wonder what would happen to him once the Sea King saw no humor in his tumbling about. Thinking that he also began to wonder just where the Sea King and his fairies got the meat they ate at meals. It was not fish—the fisherman knew fish. It was not fish. It was almost, but not quite… pork? What did happen to all the sailors lost at sea? All the sea travelers that drown?

The fisherman had not partaken of any feasts once he started asking those questions and also really wished that he had started asking those questions earlier. Because he could not think of an answer that he wanted to think about at any length. And sometimes he recognized hunger in the eyes of the creatures who watched him while he danced and tumbled. The hungriest eyes of all were those of the Sea King. The very evening the fisherman’s wife dropped her hook in the water, the Sea King presented the fisherman with silken reins and harness.

“Tomorrow morning,” the Sea King told him, “I shall harness you to my carriage and you’ll give me a merry ride around my lands.”

This frightened the fisherman very much. He determined that he must escape before the dawn. So he put as much spirit as he could muster into his antics. He sang and danced and tumbled and fell as hard as he could, aiming to wear the king out with laughter. It worked—or so it seemed—because shortly after his performance the Sea King fell into a slumber and the fisherman sneaked away.

Softly the fisherman strode over the golden sand—through the mighty Hall, spacious as a wide meadow; he slipped through the golden hedge, carefully parting the branches of pearls; and when he came to where the sea stood up like a wall the fisherman dove into the water.

But it is far—terribly far—from the Sea King’s fastness to the world above! The fisherman swam and swam; but how was a poor fisherman to swim the depths of the sea?

He felt as if the sea was piling itself up above him, higher and higher, and heavier and heavier. His body ached, his lungs burned for air. Black spots started appearing at the edges of his sight. Just as he was about to give up and take the breath that would doom him to be the Sea King’s dinner, the fisherman reached up and felt a hook catch his hand. He grabbed onto it with all the strength he had left and tugged, pulling himself up as he felt someone on the other end reeling him in.

Anything, he thought, is better than going back to the Sea King.

Of course, on the other end of that hook was the fisherman’s wife!

She reeled him in and he swam up and they met each other with laughter and tears and apologies on his part and forgiveness on hers. The fisherman grabbed his wife and held her and squeezed her, his heart full to bursting. Then he scooped up their son who laughed with joy at seeing his father again. Well, that, and being tossed in the air. There were kisses and cuddles. The fisherman vowed in his heart of hearts to never take his family for granted again and told his wife how miserable and afraid he’d been these last few months and how sorry he was again for being such a fool. And wife, for her part, forgave him yet again and told him of her journey and showed him her net which is such a useful thing which the fisherman agreed for it seemed quite brilliant.

Of course, they were still stuck in the unknown sea and didn’t know how to get home. The fisherman’s wife thought maybe they could go back through the caverns, but no matter which way they sailed she couldn’t find them. And so they sailed in circles for many nights and days. The fisherman began to fear that they were being hunted too. He’d swear he saw the Sea King or the Sea King’s servants, eyes just above the water, but whenever his wife turned to look there’d be nothing but ripples. The fisherman feared he was going mad again, but his wife told him that she believed him. There was a laughter on the wind that spoke of magic and mischief.

One day turned to two turned to three and finally, finally the fisherman’s family found themselves before a dark wall of stormclouds. The fisherman wanted to turn back, but his wife convinced him to forge ahead. They sailed into the cloud and found within it a wall of rock with a crack in it just big enough to fit their boat. Within the rock was a cavern and the Golden Bee who flashed with lightning and rumbled with thunder.

The Sea King, who was indeed stalking the fisherman shouted to the bee, “Stop them! Don’t let them through!”

The fisherman quaked with fear but his wife brandished her clever net at the bee who saw it and remembered the feeling of being captured so flew into the far corner of the cavern until that awful woman with her terrible net had passed by and gone away.

The family sailed on until they came to another wall of dark cloud and another crack in a rock just big enough to fit their small boat. They sailed through and the fisherman’s wife hid herself, her husband, and their son under her large cloak of feathers and snakeskin.

“You don’t see me!” she shouted to the Mother of All Birds, “All you see is this little boat with a cloak of feathers and snakeskin, right?”

The great bird cackled and asked, “Did you at least find your husband?”

“I know we haven’t met, but you don’t see me either. Hello!” shouted the fisherman.

The bird cackled again, rather pleased the little human she’d met earlier proved clever enough to get her way.

The Sea King, having caught up with them again, shouted for the bird to raise a storm to stop the boat and the family within.

The bird squacked and waved her wings. A great storm, like nothing the world had ever seen, rose, but the wind before the storm sped the little boat safely away.

“Odd, that,” said the bird to the Sea King, “who knew something like that could even happen? I certainly didn’t.”

The fisher family soon found themselves in front of the third crack, the first cave, and one very large snake. Again the fisherman’s wife hid them beneath her cloak of feathers and snakeskin.

“You don’t see me!” she shouted to the Mother of All Snakes, “All you see is this little boat with a cloak of feathers and snakeskin, right?”

The great snake snickered and asked, “Did you at least find your husband?”

“I know we haven’t met, but you don’t see me either. Hello!” shouted the fisherman.

The snake snickered again, rather pleased the little human she’d met earlier proved clever enough to get her way.

The Sea King, having caught up with them again, shouted for the snake to stir up a wave to capsize the boat and the family within.

The snake sighed and whipped it’s tale and stirred up a wave the likes of which has never been seen in the world before or since, but somehow rather than crashing down on the little boat, the wave lifted it up and carried it speeding far away from the Sea King’s domain and the Unknown Sea. Within seconds the family was far beyond the Sea King’s reach.

“Odd, that,” the snake said to the Sea King, “who knew that something like that could even happen? I certainly didn’t.”

The Sea King bellowed and went back to his keep to think of clever ways to punish the guardians of the Unknown Sea for failing in their duties by not just letting a human into the Unknown Sea but letting her back out again.

The wave carrying the fisherman’s wife’s boat carried the family all the way back to their house, gentling as it got nearer so as not to destroy the place. There was much rejoicing when the family got home, though some months went by before the fisherman felt safe enough to go out in his boat again. When he did he brought home far more fish, enough to sell, because his wife had taught him to use her net. His bone hook he dulled and hung around his neck as jewelry to remind himself of what a fool he’d been and of the trouble his wife went through to catch him again. He vowed to prove himself worth the trouble and in the end he did.

Just ask his wife.